A common assertion made by investors these days, both novices and pros alike, is that stocks are expensive after the fastest and sharpest recovery from a bear market in modern history, which itself followed one of the fastest/shortest bear markets in modern history earlier this year. With the S&P 500 having just touched a fresh all time high, surpassing the February peak achieved after an epic 11 year bull market and with the S&P TSX Composite closing in quickly on it’s all time highs as well, we will address this assertion more thoroughly and thoughtfully.

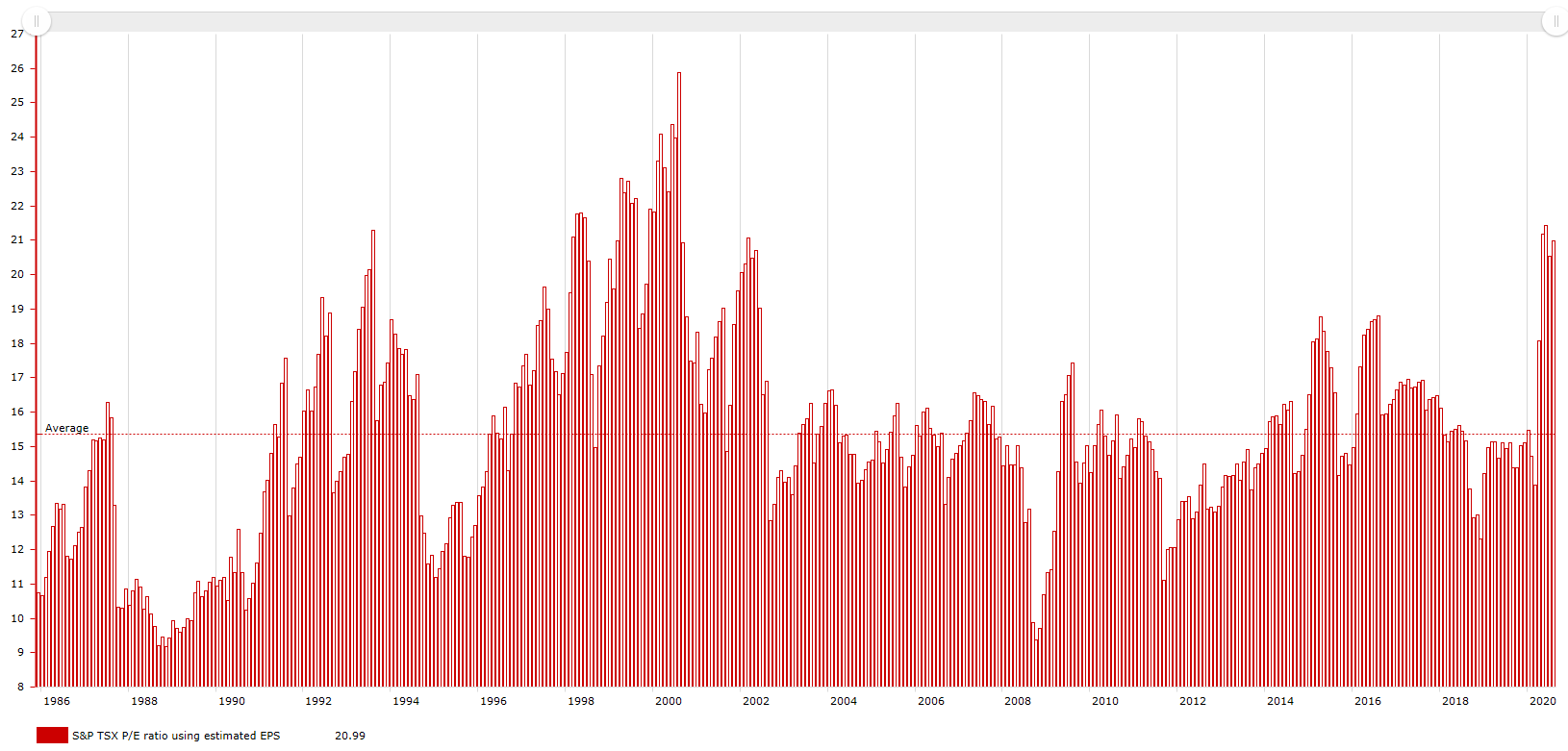

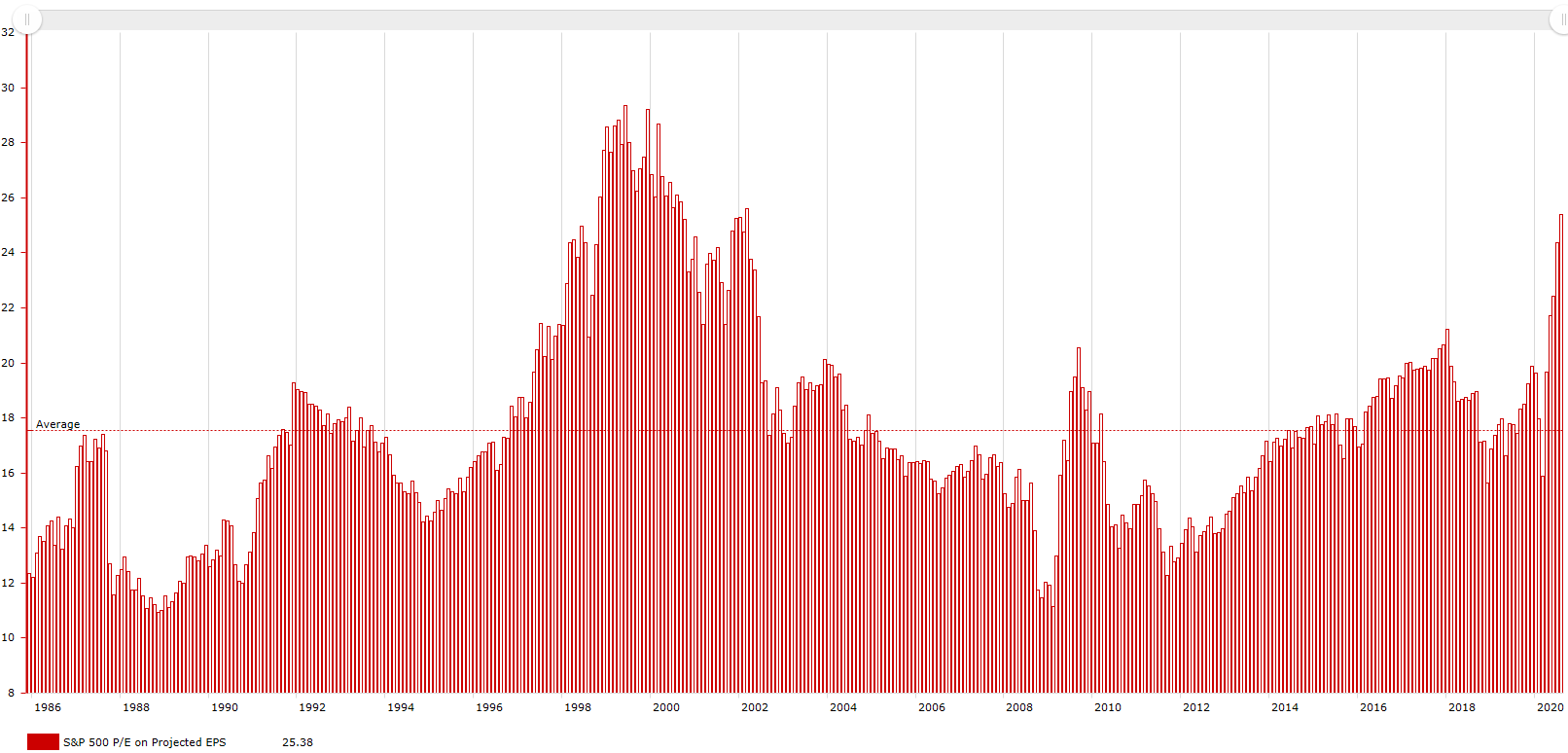

In investing, as with life in general, a little knowledge can be very dangerous. It is all too often the case that when we hear the phrase, “stocks are expensive”, someone has done about 30 seconds of analysis, looked at the price to earnings ratio of the S&P 500 or S&P TSX Composite and concluded that the ratio is elevated (which it is) and thus stocks are overpriced. Shown below in red is the historic price to estimated earnings ratio for both the S&P TSX Composite and the S&P 500. There is no denying that at 21x forecast earnings and 25x forecast earnings, both markets are sporting P/E ratios well above their 35 year averages of approximately 15x and 18x, respectively. But here’s the problem with stopping the analysis there and drawing the superficial and potentially unwarranted conclusion that stocks are expensive: earnings are procyclical…they rise and fall sharply with the economic cycle. We can do much better than this.

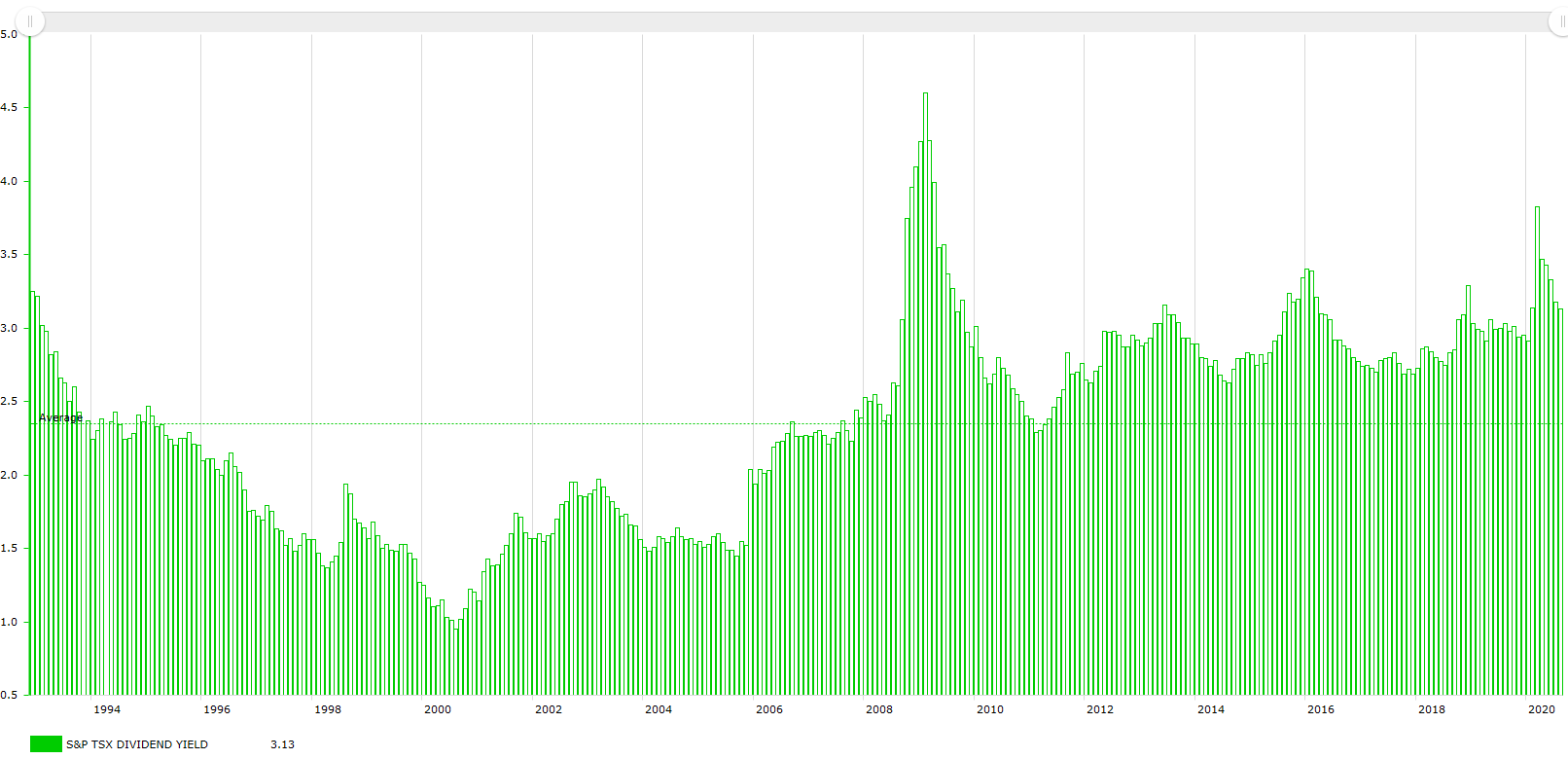

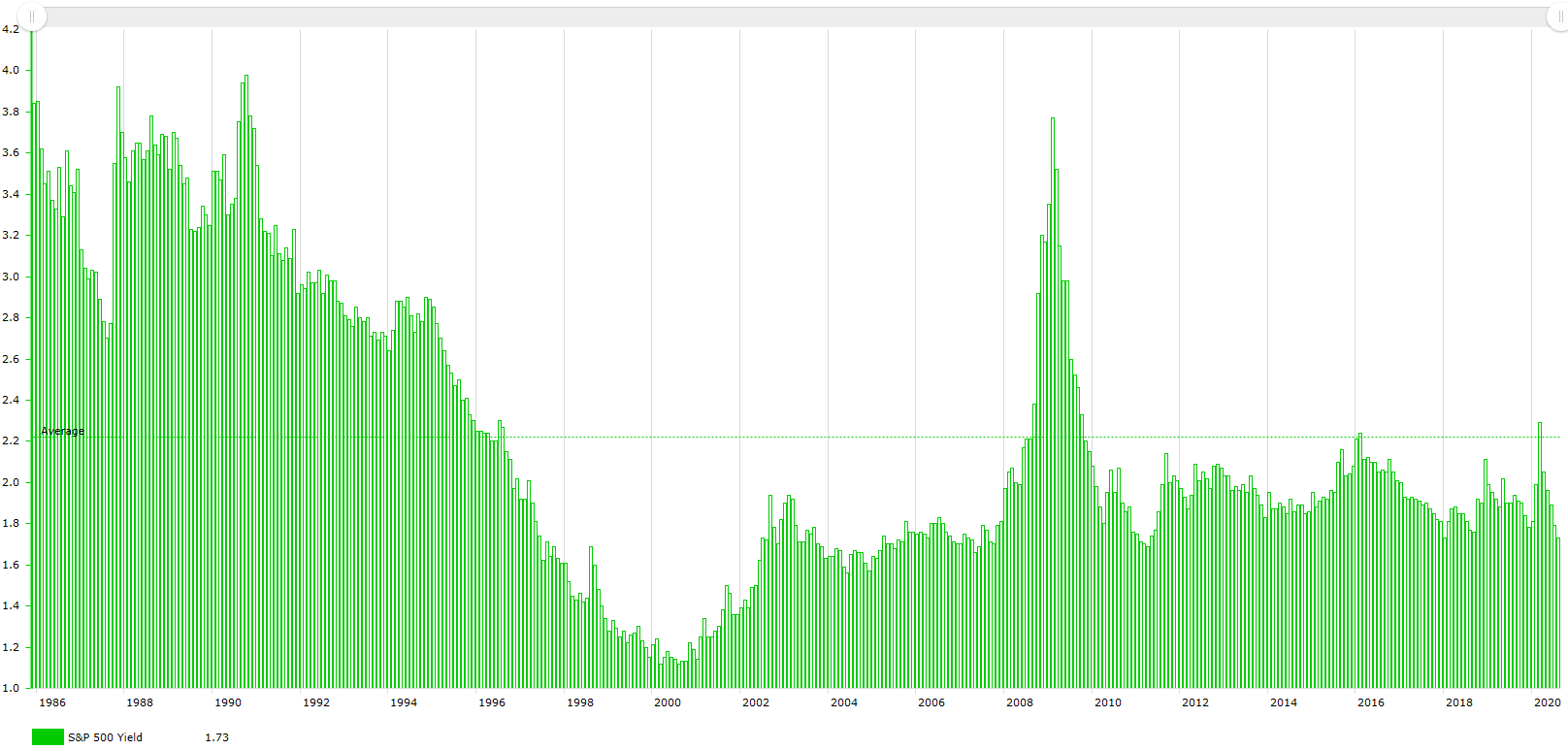

With the economy emerging from the deepest recession in 100 years, it comes as no surprise that 2020 earnings are not just going to be “bad” - they will be downright “ugly”. But that tells us nothing about their stream of earnings in 2021, 22, 23 and on into the future in perpetuity. So, rather than gauging whether stocks are over or undervalued based on their clearly very cyclically depressed 2020 earnings, investors need to look at other valuation yardsticks that are much less prone to the vagaries of the economic cycle, namely dividends, book values and sales. Because of the operating leverage in most companies, which in layman’s terms means that they have fixed costs, and because shareholders get paid last, behind trade creditors, landlords, employees, bondholders, tax authorities, etc., when sales turn down even slightly, earnings usually turn down much more dramatically. Similarly, dividends, which boards of directors are extraordinarily reluctant to reduce except as an absolute last resort, and book values which represent the cumulative shareholders’ equity raised and earnings retained over the life of the company are much, much less cyclical than earnings, and accordingly are useful signposts of value at economic extremes. Shown below in green is the dividend yield for both the S&P TSX Composite and the S&P 500. The dividend yield on the S&P TSX Composite currently stands at 3.13%, well above both the yield on risk free assets of essentially zero and its own 35 year average yield of 2.4%. The yield on the S&P 500 of 1.73%, however, while also well above today’s risk free rates is below it’s long term average of 2.2%.

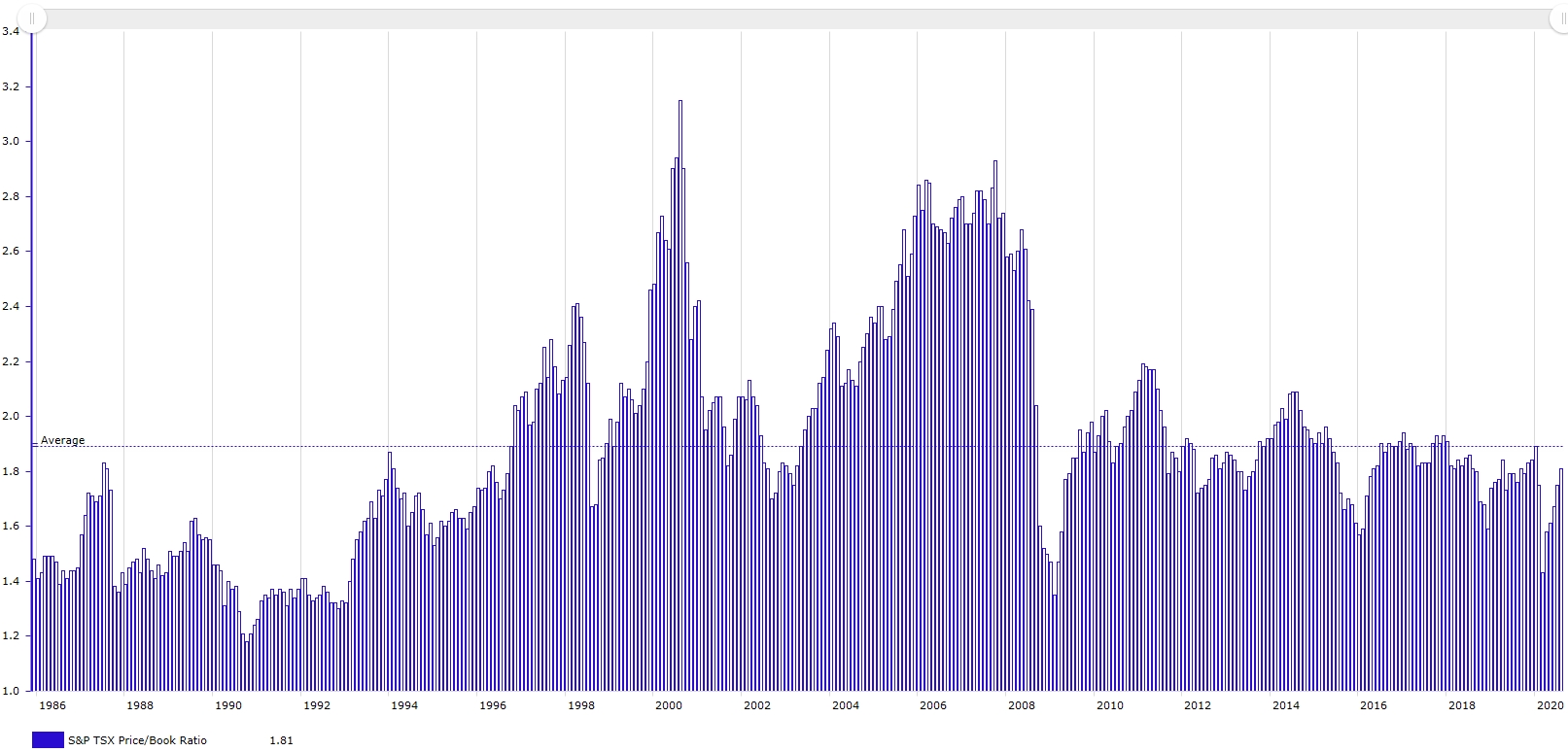

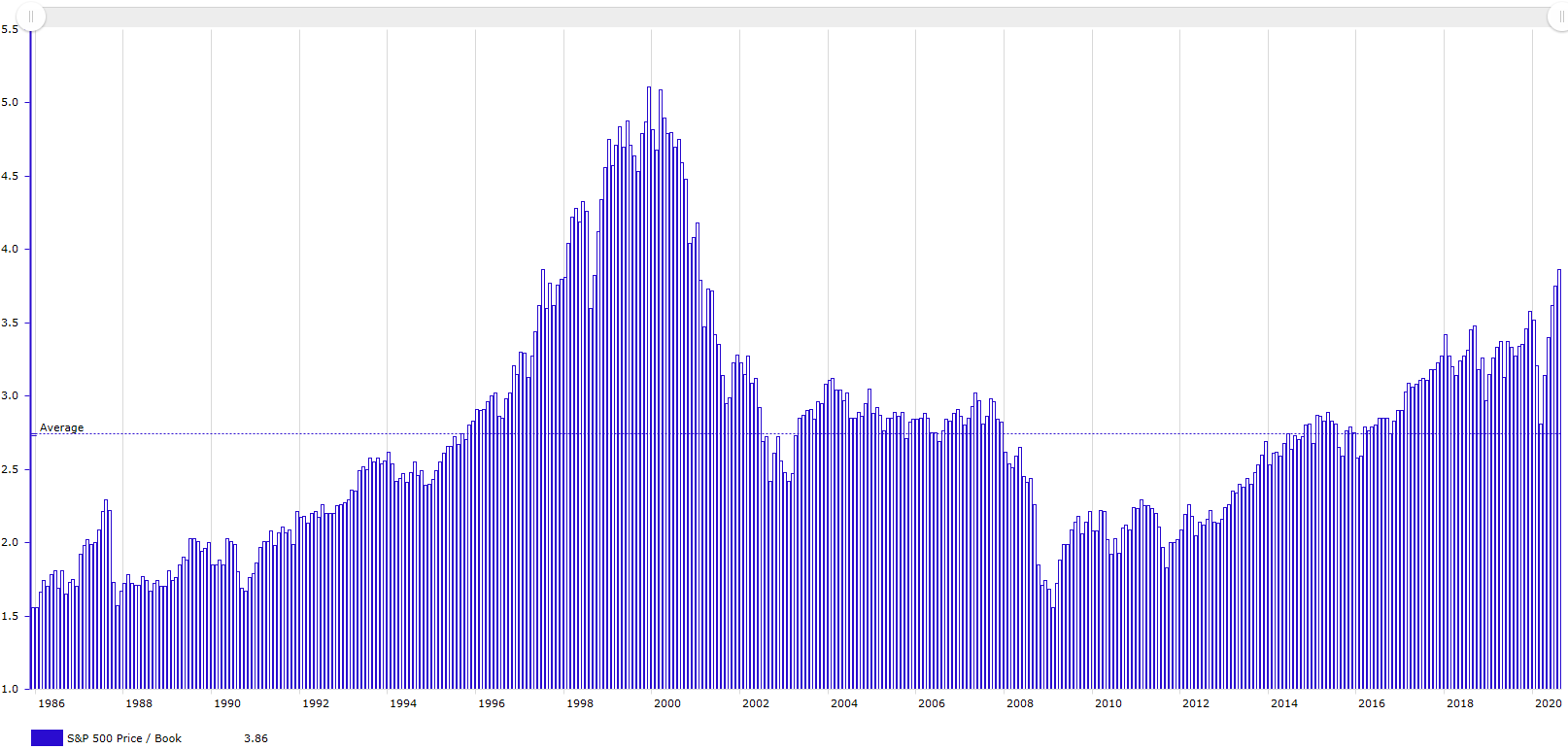

Shown below in blue is the price to book ratio for both indices. The price to book ratio, which measures the ratio of market value to accounting value of companies’ net assets stands at 1.81x for the S&P TSX Composite and 3.86x for the S&P 500. In the case of Canadian stocks today’s price to book ratio is just slightly below the long term average of 1.9x whereas U.S. stocks are trading well above their long term average price to book ratio of 2.75x.

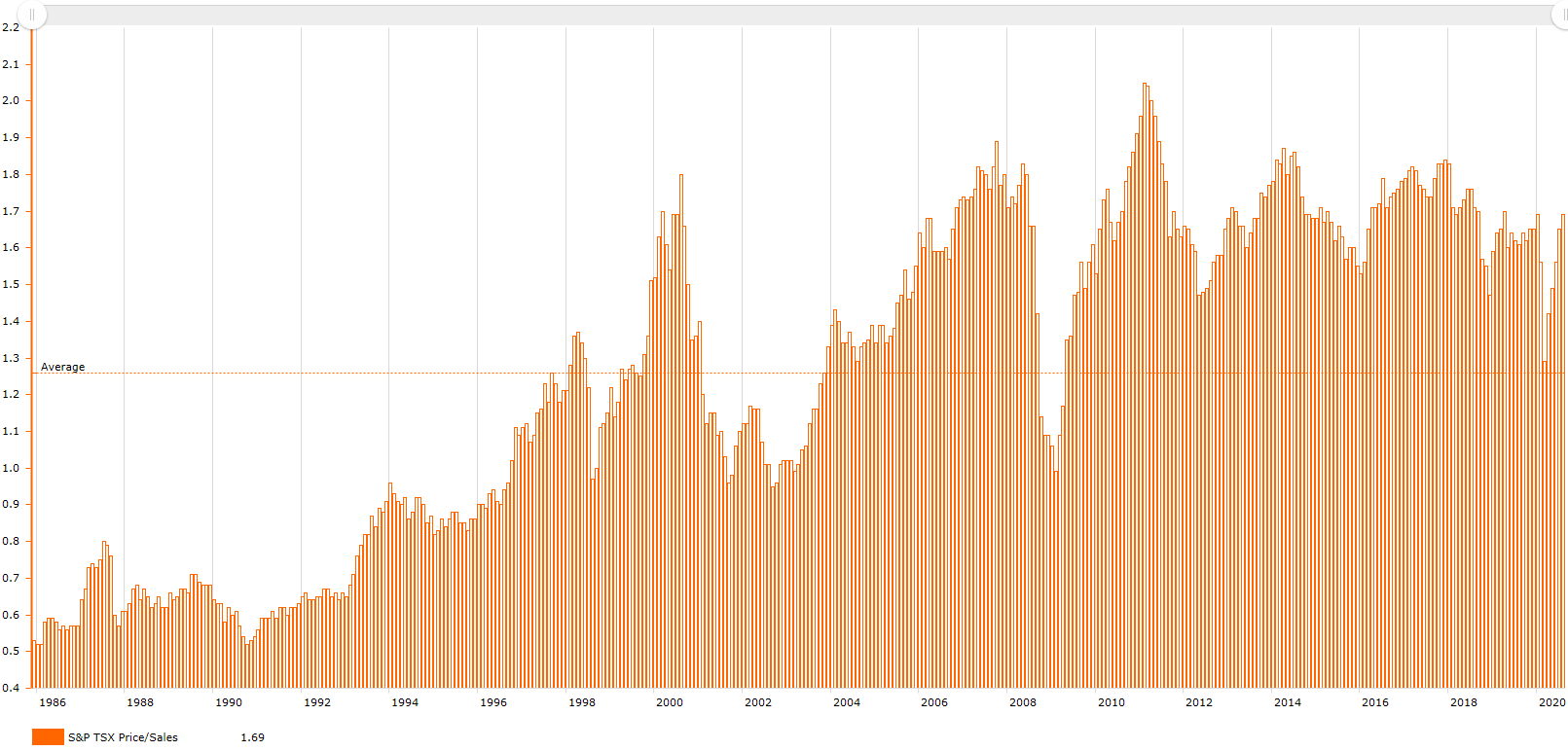

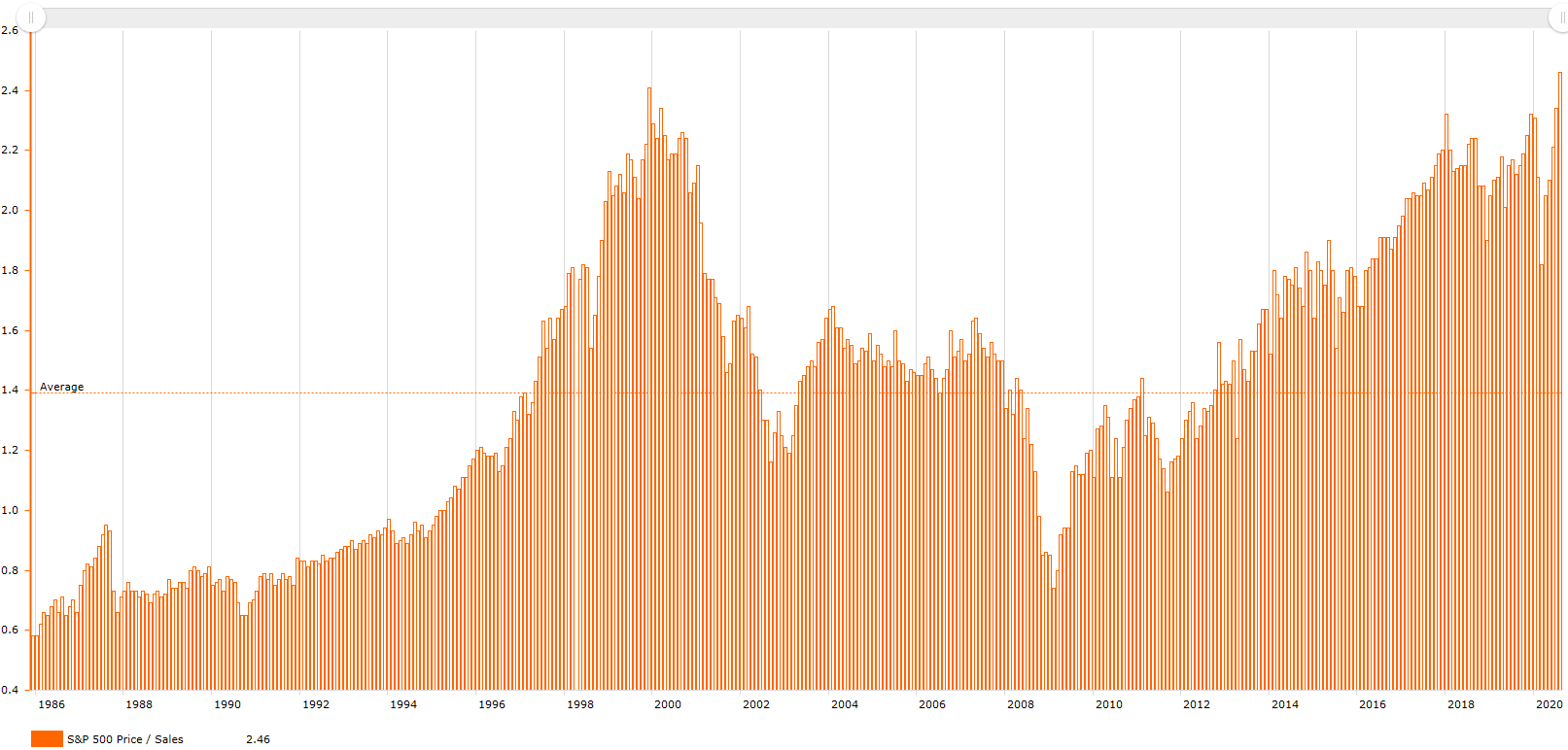

Finally, shown below in orange is the price to sales ratio for each country, with Canada trading at 1.69x and the United States trading at 2.46x, both elevated relative to their respective long term average price to sales ratios of 1.26x and 1.39x.

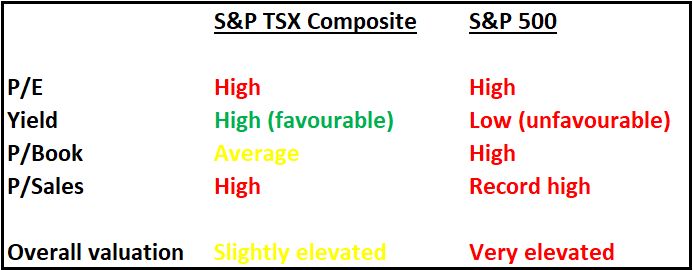

Ratios are shorthand, quick and dirty measures of valuation. A deep analysis, of the type we would do at the individual company level when evaluating a business for investment involves forecasting financial results several years into the future to gauge whether the stock offers good value. It’s difficult to do that for the entirety of corporate Canada and America, so we often rely on ratios as a proxy for overall valuation in the marketplace, but it is simplistic, sloppy and lazy to look at just one measure, particularly at an economic extreme, knowing full well that the metric being evaluated is volatile and procyclical. By broadening the analysis, what we learn is more nuanced and is summarized in the table below.

And as a last word on valuation, undervaluation and overvaluation are neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for a bull market or a bear market to unfold. Expensive stocks can and often do get more expensive (i.e. Shopify), and cheap stocks can and often do get cheaper (i.e. Laurentian Bank). Two important mitigating conditions to today’s somewhat high (Canada) and very high valuations (U.S.) are monetary conditions (i.e. zero interest rates, which make risk free assets unappealing and drive money into stocks), and profitability, which in the case of American companies as recently as a year ago reached an all time high of 19%, as measured by return on shareholders equity with business models becoming increasingly efficient, scalable and “asset light” and as the benefits of corporate tax reform flowed to the bottom line.

So, when you next hear an “expert” boldly proclaiming that stocks are “overvalued”, “undervalued”, “expensive” or “cheap”, supported by little more than a single flimsy ratio, ask yourself if they’ve really done their homework and whether the answer really is black and white or if it might just be more nuanced as we’ve shown here.